At first glance, kasuri looks simple. It’s a cotton fabric that comes in various shades of blue with recurring patterns in white. Next to the bright colors of a silk kimono, you’d be forgiven for thinking that this textile is, frankly, plain.

You’d be mistaken. Behind kasuri’s modest appearance is a remarkable process that begins with raw cotton and indigo leaves, and ends with a handful of craftsmen and women applying skills honed over centuries.

You’ll find the first clue to kasuri’s hidden magic on the back of the fabric. Turn a piece over and you’ll notice that the “wrong” side looks strikingly similar to the “right” side. That’s because, unlike most of the patterned materials we wear today, kasuri’s designs aren’t printed on after the fabric is made, but before.

While some workshops have opted to modernize production through mechanization, traditional kasuri production is still practiced at a number of workshops in Kurume, Fukuoka Pref. With 23 manufacturers, Kurume is one of the largest remaining centers of kasuri in Japan. Some of the workshops are open to visitors by arrangement – so you can see for yourself how a few bundles of thread become a touchable, wearable piece of Japanese heritage.

Step 1: The pattern

Traditionally used to make everyday wear, Kurume kasuri typically features simple designs: bold geometric shapes, for example, tiny diamonds, blocky flowers, or showers of thin lines that represent rain.

Much of the Kurume kasuri produced today still incorporates the same patterns. Some manufacturers, though, have begun experimenting with new designs, from gingham checks to a surreal pattern of disembodied eyes and noses borrowed from Japanese dolls.

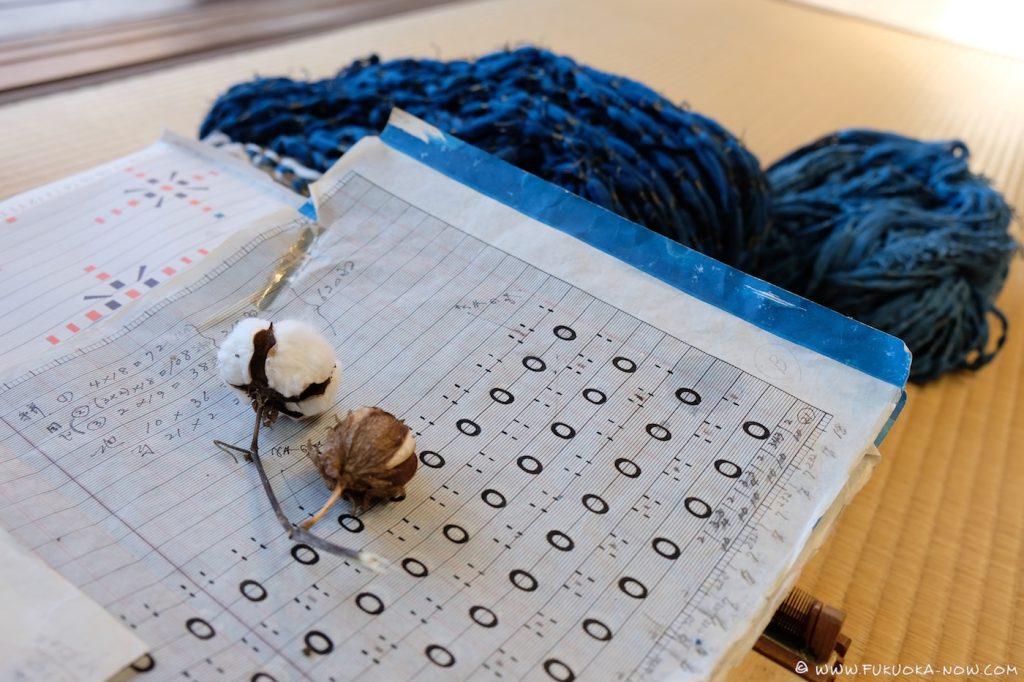

These patterns are transferred onto what looks like a long strip of graph paper, where each tiny square represents a fraction of the finished fabric. Master tyers will use the layout to calculate exactly which part of each thread should be dyed, and which parts left white.

Step 2: Tying

Kurume kasuri has always been made of cotton, just the thing for making durable, breathable clothes. The cotton arrives in Kurume in its natural creamy white color – the same that you see forming the pattern in the finished cloth.

When you’re dyeing the thread, you need to cover up the parts that should remain white and leave out the parts that’ll be colored blue. The traditional way of doing that is to gather cotton threads into bundles and stretch them out taut, line them up with the paper pattern and knot hemp around the parts you want to stay white.

It’s a job for a specialist craftsman, who then hands the knotted bundles over to the next artisan – the dyer.

Step 3: Dyeing

The earliest kasuri got its vibrant blue color from indigo – a natural dye made from the leaves of the indigofera plant, which is native to the tropics. The most traditional of Kurume’s manufacturers still use the same technique today.

Indigo leaves are harvested, dried and fermented until they form a paste, which dyers brew up into a liquid that will ferment a second time. Each dyer’s blend is different: part wood ash or seashells to make the mixture alkali, part starch syrup or sweet sake.

Master dyers – it’s traditionally a man’s job – make several vats of dye with different concentrations of indigo, which they’ll use for around six to eight months at a time. The mixture continues to ferment all the while, its color gradually fading over its lifespan. Experienced dyers can tell how far advanced the fermentation is by tasting a little of the liquid.

Dyeing itself is an intense physical process that involves dipping a bundle of thread into the solution, wringing it out and beating it against the floor to expose each thread to oxygen, without which the color won’t take. The process is repeated as many as 40 times to achieve the darkest blue-black.

Other Kurume dyers have opted for the less labor-intensive – and expensive – alternative of chemical dyes and modern machines, which speeds up the process to a matter of minutes. It also creates the rainbow of colors in which contemporary kasuri now comes.

Whichever process dyers use, the final step is rinsing and drying. It’s this stage that creates one of Kurume’s most memorable views: bundles of blue and white thread hanging outside in the sun, slung over bamboo poles or stretched out across the fields to their full length – nearly a kilometer.

Step 4: Weaving

If the dye house was originally men’s domain, the weaving workshops were run by women. The work here is mind-blowingly intricate: first the bundles are separated out into hundreds of individual threads, then these are aligned and wrapped around wooden shuttles that the weaver will use to interweave the weft (across) threads with the warp (down) threads. Depending on the design, patterned weft threads will be woven with plain warp threads or vice versa, or, in the most complex versions, both weft and warp are patterned and must be matched up on the weaver’s loom.

Kurume’s weavers use traditional narrow looms that produce cloth no wider than 40 cm: the width required for a Japanese kimono. These looms are either entirely hand-operated, powered only by a foot pedal, or mechanized, so that the shuttle moves back and forth automatically. Either one requires constant attention from a skilled operator.

Years are spent learning each craft but, however skillful, no weaver can match each thread perfectly. Tiny variations create a distinctive feature: slightly blurred edges to the patterns. A flaw, perhaps – but also one of Kurume kasuri’s charms.

Kurume Kasuri Events – 2018

Though Kurume kasuri is rooted in tradition, it is used to make beautiful, everyday clothing. If we’ve piqued your interest, then read on to learn where you can see kasuri first hand. 2018 is a special year. It’s the 150th memorial year of Ms. Den Inoue (1788-1869), the pioneer of Kurume kasuri. At thirteen years of age she noticed a white spot on a discolored part of her clothes and came up with the idea for a woven fabric which became known as Kurume kasuri. On her 150th memorial year there will be many special events including these.

21st Kurume Kasuri Ai (Indigo) • Ai (Love) • Deai (Meet) Festival / 久留米かすり 藍・愛・で逢いフェスティバル

A festival for kasuri lovers with stalls selling the latest in kasuri style. Workshops will display new and classic Kurume kasuri items in the Kurume kasuri fashion show. The largest Kurume kasuri event in Japan. There will be a Den Inoue display too.

• 3/17 (Sat.), 3/18 (Sun.)

• 10:00~17:00

• Free entrance

• Jibasan Kurume

• 5-8-5 Higashi-Aikawa, Kurume

• 0942-44-3701 (Kurume Kasuri Association)

Den Inoue 150th Memorial Service / 井上伝女 150回法要

Open to the public. A statue in honor of Ms. Den’s achievements can be seen here where she is buried.

• 4/26 (Thu.)

• Tokuunji Temple

• 66 Tera-machi, Kurume, Fukuoka

Hirokawa Kasuri Matsuri / 広川かすり祭

Two days where you can buy Kurume kasuri items at discounted prices and visit workshops on free buses. See and enjoy the Hirokawa area!

• 9/15 (Sat.), 9/16 (Sun.)

• Hirokawa Industry Exhibition Hall

• 1164-6 Hiyoshi, Hirokawa-machi, Yame-gun, Fukuoka

• 0943-32-5555 (Hirokawa Tourism Association)

Kasuri Home Visits in Chikugo / 絣の里巡りin筑後

Two weekends where Kurume kasuri studios are opened to the public. Stroll through the studios, watch the craftsmen and explore kasuri’s tradition. Held every Jun. and Nov.

• 6/2 (Sat.), 6/3 (Sun.) and 11/10 (Sat.), 11/11 (Sun.)

• Headquarters: 730 Kumano, Chikugo, Fukuoka

• 0942-53-4229 (Chikugo City Tourism Association)

Kurume Kasuri Discovery Tour 2018 by Fukuoka Now

Join Fukuoka Now’s tour of Kurume kasuri workshops (and also visit a local sake brewery) on Feb. 3, 2018 – click here to learn more and signup! English guide included.

Original Text by Jess Phelan. Updated Dec. 2017.